A Good Loud

Crystal Radio Design With Some Justifications And Digressions

If you're enjoying these pages and you

have an interest in hobby type electronics or repair jobs, you

might like to visit my other website www.usefulcomponents.com,

where there are details of some components for sale and good radio

kits.

Or, Yet Another Crystal Set Radio

Design

If you're looking for a kit of modern parts that's quite sensitive

and easy to build I heartily recommend the HJW

Electronics Choccy Block Crystal Set Radio Kit, which now

includes a very good single

transistor radio cheating option. That design is

optimised for more practical aerial wire lengths.

This page was created in 2010. There are some useful updates lower

down.

I've discussed elsewhere my experiences recreating the full

version of the G.C. Dobbs Ladybird

Book "Making a Transistor Radio," Radio. But the first thing

in the book was a crystal set design, to ease the young radio

constructor into things gradually. This was what I tried to make

first as a kid, and had zero success with it for months if not

years, before figuring out one or two things by trial and error.

But first let's fast-forward to the present to see one way to make

a quite good crystal set radio if you have a long aerial.

I've tinkered with this over the years, and always had quite poor

results due to various things, but the main one has always been a

lack of space and location in which to erect a proper long wire

aerial. Well, while walking back from lunch from one of my works

buildings to another, I chanced to look skyward and noted the

four-storey nature of these buildings and the adjacent

multi-storey car parks. Tall buildings, with easy access to a

rooftop balcony on one, and the top floor of the car park on the

other, about 80 metres apart, on a private site? Hmmm. You can see

where this is leading. So I decided that slinging up a nice wire

aerial over the quiet Christmas season shouldn't attract too much

attention and would be a good proving ground for a decent crystal

set. But first, we need a design for this decent crystal set.

There's no shortage of designs on the web. Double tuned designs,

designs with exotic spider web coils, double-diode detectors,

voltage doubler detectors, low impedance headphones with audio

transformers; The choice is endless. So what I'm going to present

here is yet another design that is nothing special but which I

quite like. I particularly like it because it is possible to

optimise it for loudness in the particular conditions and

components that you find yourself with. Once you find the optimum

matching points by sliding the coils up and down, you then know

that it's as good as it's going to get, and you can stop fiddling

with it and go and do something more useful.

Parts That I Used

1 long ferrite rod from an old

transistor radio, about 7 or more inches long if you can get it.

2 medium wave coils from an old transistor radio (but see text)

1 aerial coupling coil from an old transistor radio

1 OA81, 1N60, or any other germanium diode from an old transistor

radio (a working one - the diodes are sometimes open circuit)

1 air spaced variable capacitor from an old radio, ideally an old

500pF whopper from a valve radio

1 100m reel of 7 X 0.2 wire

Here's The Circuit

This consists of three coils fitted onto the ferrite rod in such a

way that they can slide up and down on it. Coils from an old radio

should already be able to do this if you scrape off the sealing

wax. The main MW tuning coil is put in the middle of the rod and

the tuning capacitor is connected directly to it. Considering the

lengths that people go to when winding these coils in order to

keep their main tuning tank free of unwanted losses, it's sensible

to keep this wiring as short as possible. You only need the

resistor shown across the headphones if it's a ceramic type. You

only need the capacitor if they are iron diaphragm or moving coil

magnetic types.

I have to digress here. As suggested above, you can buy really

exotic coils made out of super Litz wire which exhibit Q factors

of 750 in a 300uH coil at 1MHz, or you could make one out of gold

plated 2 inch diameter copper tubing or some such. But there's a

limit to how much Q you could ever actually want in a crystal

radio coil, and it's worth going into this in some detail to see

how far we might want to go down the coil-winding craziness route.

High Q in an LC tank gives sharper tuning, which we want to some

extent. When we start taking energy out of the tuning tank in

order to actually listen to it, whatever Q you started with will

drop and inevitably the tuning gets broader. So what Q do we

actually want in the finished radio? Taking the tuning tank on its

own for the moment, lets assume a typical MW coil of 370uH tuning

into 1MHz using a 68pF capacitor. The RF bandwidth of an AM radio

station in Europe is about 12KHz, so you would never want to go

any narrower than that or you would start to filter out the treble

content which provides some of the loudness. 12kHz bandwidth at

1MHz equates to a Q of 83 and that would be equivalent to a

perfect LC tank with a 195kOhm resistor in parallel. Now the

aerial coupling coil and output coupling coil will load the

system, reducing the Q. When the three coils are coupled

optimally, this boils down to having three equal resistances in

parallel which are the lossy parts of each circuit, aerial, tuning

tank and output. It's these three resistances in parallel that in

the complete system should never be more than 195kOhms. So, each

of those resistances need never be higher than 195k X 3 which is

585 kOhms.

So if the perfect tuning tank had this made-up 585K Ohms across

it, what is the Q? The answer is 2.pi.Fo.C = 254.

I still haven't answered the question of how far into coil-winding

craziness we need to go to get a decent loud crystal set coil. So

I measured the Q values of LC tanks that you can make with some

reasonably available parts.

a) A standard wire coil with spaced turns on a ferrite rod from a

1960s transistor radio. Q = 173 (+/- 20%?)

b) A coil made from 7 X 0.2 close spaced hookup wire in a double

pile on an old ferrite rod. Q = 98 (+/- 10 %?)

c) A modern Litz wire MW coil on a ferrite rod. To Be Measured

d) A coil made from 7 X 0.2 hookup wire wound on a cardboard box.

To Be Measured

e) A coil made from 5mm diameter copper sheathed coax cable on a

cardboard box. To Be Measured

The ferrite rod has some losses in it of course, as all magnetic

cores do. But this is partly made up for by the fact that you need

much less wire in the coil to get the same inductance. Less wire

=> less resistance loss.

All these were measured by making a tank circuit using short

connections to an airspaced radio capacitor at about 1MHz using a

10 MOhm scope probe. I induced a signal using very slight

inductive coupling from a signal generator and varied the

frequency either side of the peak until the voltage was 1/root2

times the maximum. The difference between those two frequencies I

took as the -3dB bandwidth, and yes, the results are approximate.

It's not easy to do it this way as the Q values get higher. The

error in the frequency and voltage measurements gets wider even

with a good digital scope with measurement averaging, as the

physical stray fields and capacitances drift around with

positioning of the human involved. Measuring higher than Q = 200

is going to be difficult in any circumstances without some special

equipment.

So, having a Q of 173, the conclusion of this so far is that the

1960s transistor radio ferrite rod and coil are getting pretty

close to the point where you wouldn't want to go any further, and

the fact that we had some small input coupling loading and a 10M

'scope probe in the system is working in our favour in that the

real Q must have been slightly higher than what I measured. The

double pile of standard 7 X 0.2 PVC covered hookup wire is still

quite good for the tuning tank. This suggests that using lesser

coils for aerial and output coils is definitely a go-er.

/digress

On the left of the tuning coil is the aerial coupling coil. One

end of this connects to your ground connection and the other end

connects to your aerial. The aerial coupling coil will typically

have something like ten to twenty turns on it. Another slight

digression worth mentioning here is that you can sometimes get a

static charge building up on a long wire aerial in certain

circumstances. Coupling into your system with this DC connection

to earth avoids this build up.

On the right is the output coupling coil and in my trial I used

another MW radio tuning coil. I will experiment with something

that doesn't need to be bought at a future date. This is connected

via the usual germanium diode to a 10nF capacitor and the

headphones. The capacitor serves to remove the residual RF from

the rectified audio signal and makes it easier to measure the

audio on an oscilloscope. In my set it made no difference to the

loudness but I would recommend to include it as it stops

radiofrequency energy going up the earphone circuit. This helps

make the tuning less sensitive to where you are sitting or how you

are moving about. Both earpieces of my magnetic type headphones

were connected in series and measured 90 Ohms DC on each earpiece

making 180 Ohms DC total. But they were quite inductive and at

1kHz measured about 1.5KOhms total.

Assuming you've built the radio as shown and connected up a good

aerial and an earth connection like a central heating radiator, if

you now move the tuning control around you should be able to tune

in the stonger MW stations, but they might be a bit quiet. You now

need to move the output coil closer to or further away from the

tuning coil until you find a maximum point. The maximum point will

be quite broad and you might find that if your aerial isn't very

long or the station is weak, you find that it is loudest when

right up next to the tuning coil. Now you need to do the same with

the aerial coil. Move it to and fro on the rod until you find the

broad point where the station is strongest. This may also be right

up close to the tuning coil. You might need to re-adjust the

tuning control while you do this as it can be changed slightly by

moving the other coils, but that effect should not be too large.

If you have a good aerial and earth then on a strong station you

should find that you need to move the output coil at least a

couple of inches away from the tuning coil for maximum loudness

and you should also find that maximum loudness is achieved with

the aerial coupling coil backed away from the tuning coil

slightly. If this is not the case, you can add a few more turns to

the aerial coupling coil. What have we done with this moving

around of the coils for maximum loudness?

What we've done here is to optimise the amount of coupling between

the three coil circuits in the system to allow maximum power

transfer between them for the conditions of your particular

components, your particular aerial system, and the frequency and

strength of the particular station that you've tuned in. The fact

that we have found maximum loudness positions on the rod for

aerial and output coils some distance away from the tuning coil,

rather than just going for maximum coupling right next to the

tuning coil is particularly gratifying. It shows that we've

reached an optimum point which can't be improved further by

fiddling with the coupling any more.

If you have a stronger station you should find that the optimum

position for the output coupling coil is further away from the

tuning coil. Why is this? That's because the output coil doesn't

load the system at all before the diode starts conducting

properly, and you need a certain amount of signal before that

happens. So a stronger station results in more output loading

because the diode is conducting too much.

Counter-intuitively, you have to back off the output coil for

maximum loudness.

Things That You'll See That Don't

Work

This crystal radio story wouldn't be

complete without me getting a bit tetchy and describing some

things that you'll see in the popular literature which either

don't work or which are pointless. Let's start with some of the

more imaginative output and rectifier circuits that you'll see.

Full Wave Rectifiers And Voltage

Doubling Output Circuits

The aim of the full wave rectifier

design is to use two diodes to rectify the positive and

the negative cycles of the RF waveform from the output coil and

store them across the output smoothing capacitor, in that way

supposedly providing more output current. Voltage doublers have

more capacitors and diodes which pump-up the voltage in a stack, a

bit like a Cockcroft ladder. You would supposedly get double the

output voltage from a given input signal across the output. And if

we were dealing with a mains transformer closely coupled to a low

impedance input winding with lots of power available, that would

be true. It would also be true in our crystal radio if we didn't

need to connect our headphones across the output capacitor in

order to listen to the output signal. Unfortunately, we do need to

listen to that signal, and remember that we've already found the

optimum coupling amount by sliding the coil up and down with the

single diode circuit. The full wave rectifier circuit simply

presents a lower impedance load by rectifiying both half cycles of

the RF. If you were to use this in the radio you've already made,

you'd just end up having to move the output coil further away from

the tuning coil to reduce the coupling into this heavier load.

This is particularly pointless when you've gone to all the trouble

of finding those high impedance headphones. From the point of view

of the tuning coil, a voltage doubler has just effectively divided

the impedance of your load by a factor of four. So what should you

do now? Go out and find some even higher impedance headphones? No.

The circuit is pointless.

Audio Transformers

This section could otherwise be called

"diode forward resistance, power loss and headphone impedance."

There used to be some rash statements in here about successfully

using lower impedance headphones without audio matching, just

relying on the radio frequency matching between the tuning and

output coils. This considered the resistance of the diode which is

only about 3 Ohms when it's conducting properly but failed to take

into account the power loss across the diode forward voltage Vf.

That power is about Vf times the current. Lower impedance

headphone means more current, so more power loss in the diode and

less in the headphones being turned into sound. So you either need

some reasonably high impedance headphones or an audio transformer

and I'll be adding more information on that in due course. See the

Crystal

Radio Set V2.

Signal Strength Versus Output

Loading

I've mentioned this already but with a

weak signal, the diode isn't conducting very much until the Vf is

approached. If it's not conducting it's not loading the system

much. You'll find that you need to move the output coil closer to

the tuning coil to reach the peak loudness. If your aerial isn't

so good, you might find that you need it close up all the time,

and the best suggestion there is to try to improve the aerial or

earth.

The Classic Crappy

I told you that I was going to get a

bit tetchy on this subject and here is the circuit diagram of what

I'm going to call the "Classic Crappy."

You'll find this touted around in kid's books, some places that

should know better like The Open University Crystal Radio, and it

is the perrenial favourite in the little educational kits that you

can buy. The output you can see is connected directly acoss the

top of the tuning coil, as is the aerial. The only thing that I'm

willing to admit about this circuit is that it will work, poorly,

in some conditions. We've already seen how important it is to get

the input and output coupling right, and it's not a small

difference that it makes, it's a big difference, as in

perhaps 20dB. That's the difference between loud, and hardly

anything at all. What do you do with this circuit if you think

it's a bit quiet, such that you have to strain to listen to it or

hear nothing at all? Well you put up a better aerial. That brings

in a bit more signal, enough to hear something, but now the diode

is starting to conduct and then the output loading is far too

strong so what should have made a big difference makes a pathetic

improvement. It's bad, and it's an example of over-simplification

to the point where something deosn't really work at all. So, if

you see this design in a text book, hobby book (G.C.Dobbs, I'm

looking at You) or on a website, ask yourself if the person

displaying it has actually tried it. Crystal radios can be quite

fun and give real useful results, not the "straining to listen to

one station in a silent room" experience that you might expect.

But you need those extra couple of coils or another way to adjust

the input and output coupling if you expect proper results, or

indeed any results at all.

I mentioned that this was my experience as a youngster. I got

around the input coupling side of this by connecting the aerial

into the top of the tuning coil with another variable capacitor.

The reduced loading allowed some actual tuning to occur with my

quite capacitive indoor aerial wires and lo, some small signal

came out into the crystal earpiece on a couple of stations with a

particular favourite (probably leaky) earpiece. But winding

another couple of coils was hardly beyond me, if only I'd known

what made a difference and what didn't!

Another slight digression. These are always the best bits, right?

The crystal earpieces that you can buy used to be made of a bit of

fine foil, with the two electrodes joining at an apex on some form

of piezo crystal and touching the foil from behind the foil side

where you would listen from with the thing stuck in your ear. The

modern ones have a piezo element much like the element found in

1980s beeping watches and I've no reason to suspect that they are

any less effective; They are probably more consistant nowadays.

But if you use a modern ceramic element earpiece, you absolutely have

to have a bleed resistor of some 100K Ohms across it as shown in

my diagram. Excuse me for putting another nail in the already

peppered Crappy coffin, but this isn't a, "Nice to have." You may

find a crystal earpiece, fundamentally a capacitor which is leaky

to AC by virtue of delivering sound to the outside world, which is

lucky enough to be leaky at DC as well. This rare device will work

in your crystal radio. But most modern crystal earpieces, and many

of the old ones, will just behave like a capacitor and charge up

to whatever peak DC voltage is generated by the diode and the AM

signal tuned in, thus creating no sound.

Again, another "The Crappy" nail. Assuming that you had a

non-leaky crystal earpiece that just charged up to peak voltage

and stayed there in silence, you might be lucky and get a leaky

OC81 diode from an old radiogram. The reverse leakage in the dodgy

diode would actually make your previously silent crystal radio

burst into life! Maybe those Mullard diodes, hand crafted by

Simonstone's or Blackburn's finest ladies in white coats were

better in the old days eh? Nope, sorry, it was just a poor design

you were building which needed an unusual component with certain

poor properties.

So, The Actual 80 Metre Long Aerial

Experiment

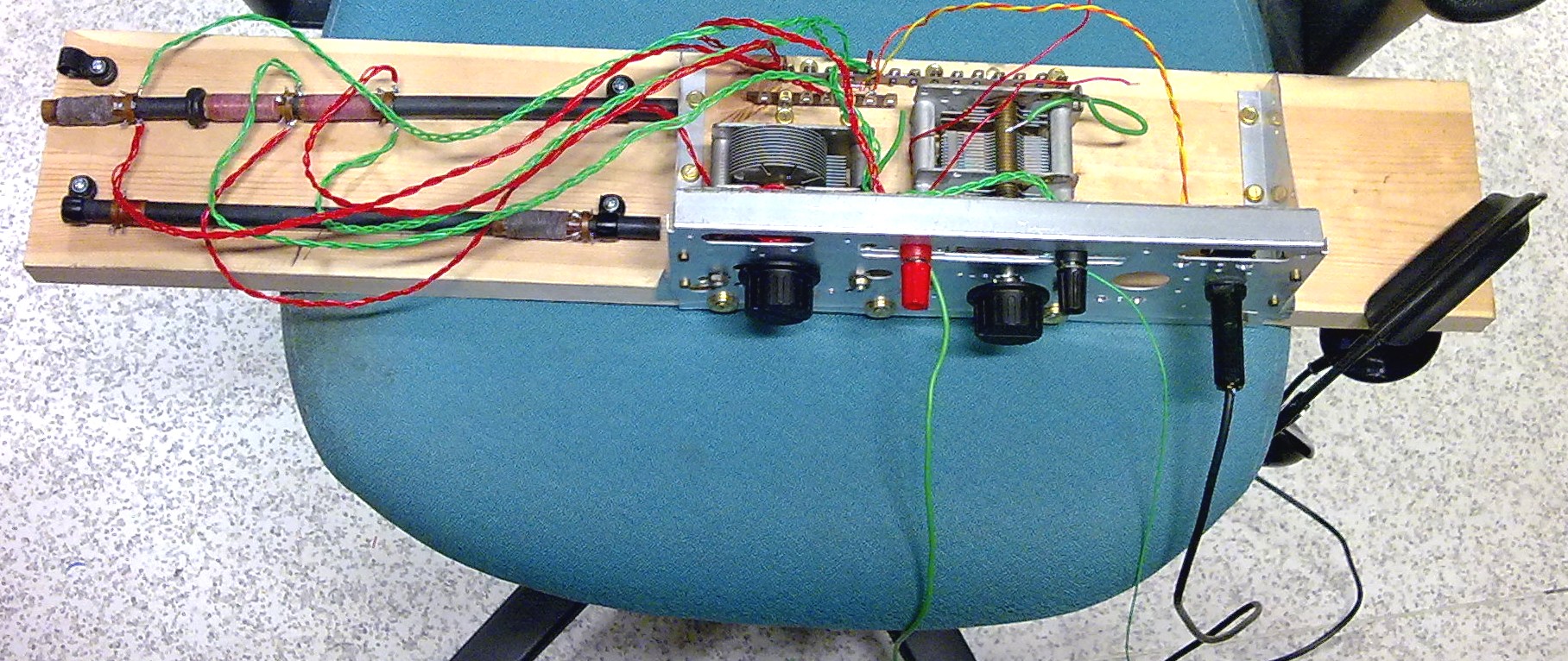

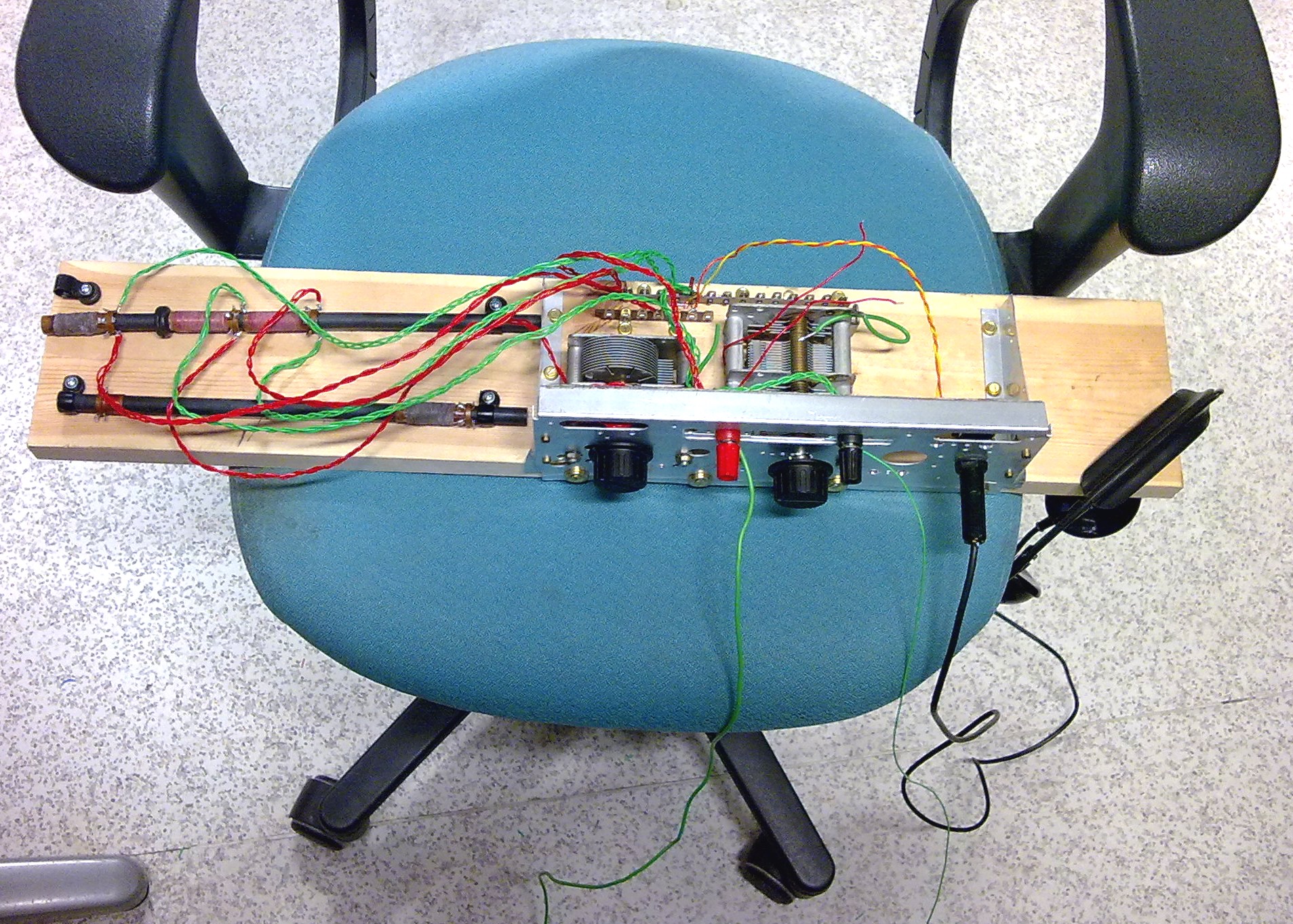

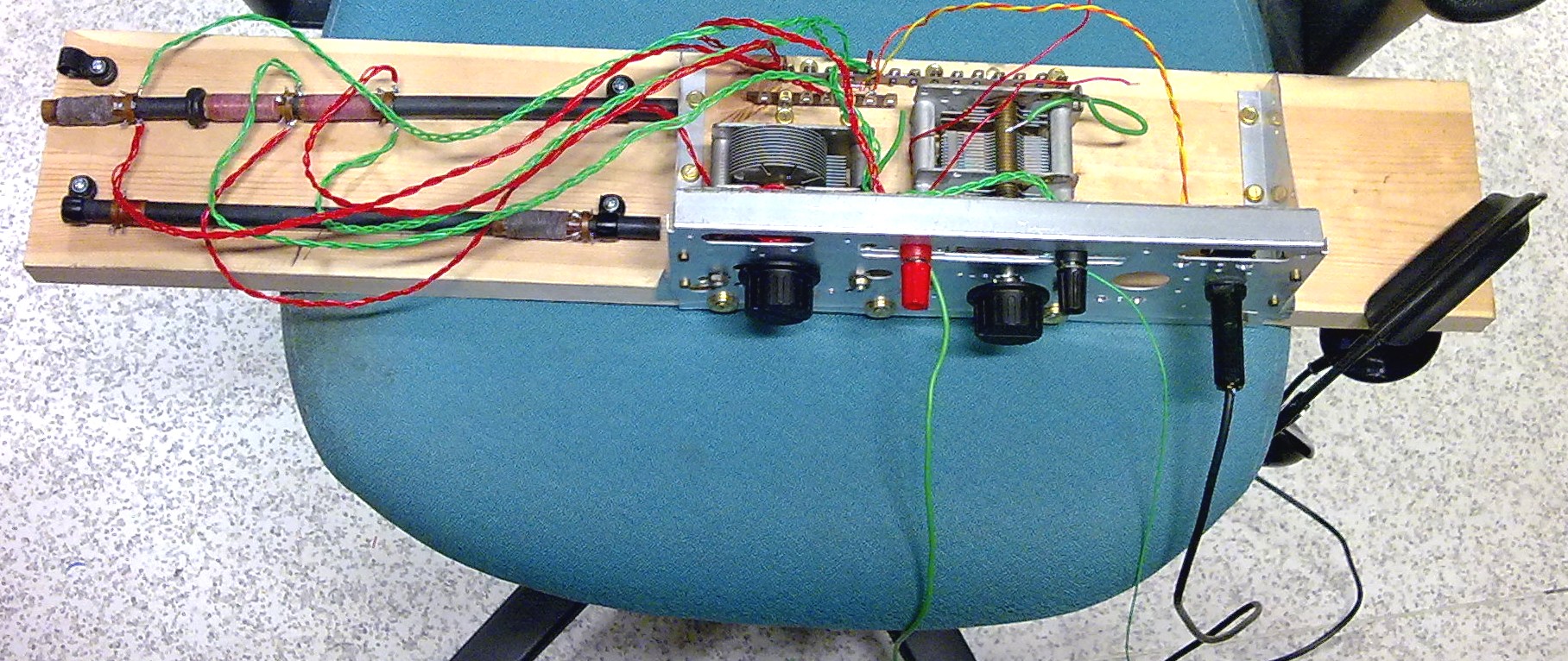

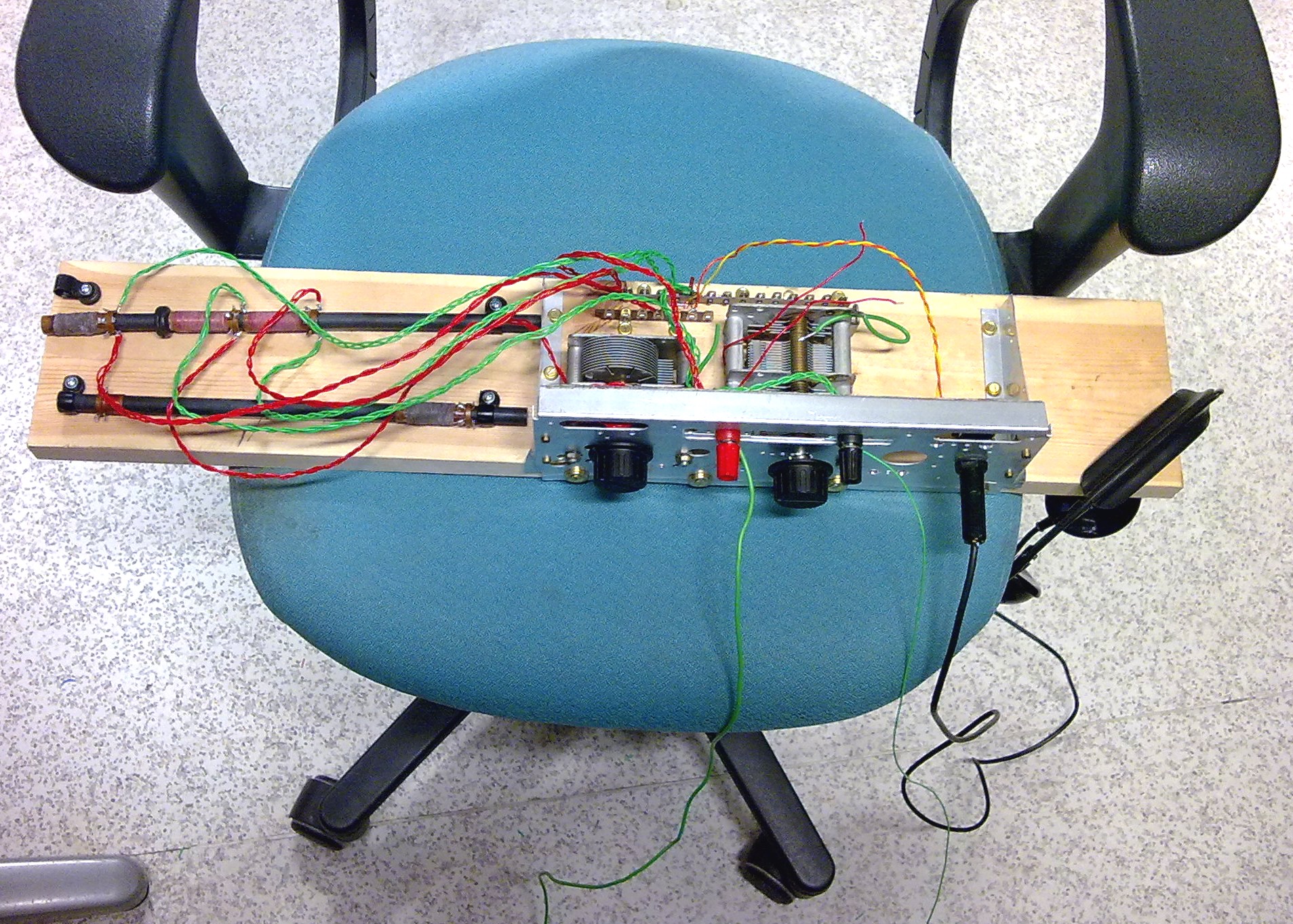

Shown here is my experimental test bed

which had two ferrite rods and two dual tuning capacitors. In the

event, only one rod and one section of one variable capacitor were

used.

Experimental Loud Crystal Radio Set Test Bed

A lot of the initial playing around that I did with this design

was using a very simple AM modulated RF signal generator coupled

into the aerial winding with a resistor of around 2K Ohms.

Initially I had a double tuned design which used both sections of

a 500pF dual gang variable capacitor. Here, the output coil was

tuned as well, but this either made setting up the tuning more

critical, or in different coupling situations made an

insignificant difference. I think that double tuned designs don't

really gain you an awful lot, and I'll leave this statement

hanging in the air as a challenge to their fans. As we've

established, tuning sharpness is dominated in the final analysis

by the need to take energy out of the system to listen to the

signal. With a decent signal, the output coil is so damped by the

output transducer that there's little to be gained by trying to

save energy by making it resonant, and if you achieved this, the

tuning point also changes as you move the coil up and down to get

the best coupling. That turns the process of tuning in a station

with best loudness into a multi-parameter procedure, possibly with

two separate capacitor controls, and the popular engineering term

for that is a "ballache."

Finally we get to how well this worked in practice, and what

aerial and earth system were used. The location was a fairly flat,

open area near junction 4A of the M3 in Hampshire, amoung a group

of office buildings. Have you guessed where it is yet? I was keen

to see just how good a crystal radio could be, having arrived at

this design and so decided to go full out for a bit of fun aerial

rigging. For convenience I had the radio in my car on a high floor

of the multi-storey car park. This car park is covered in a metal

lattice structure that was once-upon-a-time intended to be covered

in green creeping plants to make it look prettier. This never

worked but the structure is well grounded to the reinforced

concrete and made a good ground connection. The aerial was about

80 metres of 7 X 0.2 PVC insulated hookup wire. Initially I threw

this reel over the side of the car park and unwound it to a point

at the ground level of the target building some 80 metres away. A

quick check showed some stations coming in pretty well, but the

aim was to string the far end up to the top floor of the target

building. The building conveniently has a balcony on top, so

pulling up the aerial wire with another length of wire and tying

it off with a long loop of insulating tape was easy. We have now

established an 80 metre long aerial wire some four floors, perhaps

25 metres off the ground. It's not made of the best wire which

would probably be several separated strands of the same thing,

like those old "Hoop aerials" that you see on pictures of ships in

the 1920s, but it's pretty good and surprisingly heavy and

stretchy enough as it is anyway without adding more mass to the

system.

Eighty Metre Long Aerial Wire Between Two Buildings

Typical Car Park Earth Bonding Point Used For The Earth

Connection

The Antenna Wire Tied Off To A Rail At The Far End

In an ideal world, you'd secure the end of the wire with an

insulator and not just tie it round the railing. In practice, when

you have that much wire length, it doesn't make a tremendous

amount of difference for a temporary set-up. I used some

insulating tape.

You Can Just See The Car On The Fourth Floor

I'm not

sure why I didn't use the top foor. Probably to keep out of the

wind, rain, and to placate security.

Is it working? Let's run back to the car park end and see!

Yes it is, and working very nicely too. The ideal output coupling

coil position is quite dependant on the strength of the station as

I expected. The fairly small number of turns on the aerial coil

meant that it was very close to the tuning coil for maximum

output, but not quite all the way there, showing that I had

optimised the input coupling too. I could separate both the main

1215 kHz and the secondary 1260 KHz Guildford transmitters of

Absolute radio (terrible name eh? Always begs the question

Absolute what...), Talk Sport, and an Asian station down the lower

end. Listening volume was very good and you wouldn't want it any

louder on the main stations. I thought that I would have a play

with using a spare LW coil as an aerial input. As it turned out,

when almost fully on the rod this coil and aerial system self

resonated at 198 KHz, dominating the MW coil and brought in Radio

4 at a level that was uncomfortable to listen to when adjusted for

maximum output. RTE1 and a French LW station could also be heard

but as the radio wasn't optimised for this mode it was harder to

get rid of Radio 4 to receive these properly. This could easily be

corrected by redesigning it for switching in a LW main tuning

coil.

Crystal Radio Set In The Car "Gertrude," The Trusty 1992

Peugeot 205 1360cc XT

The best car eva:)

Loudspeaker Operation

Ultimately what I would like to try would be to connect a very

large, efficient PA horn speaker to the output and make a little

self-powered arty listening post on the top of the car park. That

way you could come up and sit outside listening to genuinely free

radio on your lunch break in the Summer. I had the 16 Ohm Adastra

PA driver available for this but hadn't got round to buying the

large horn to attach to it yet. So I tried a standard 8 Ohm

elliptical speaker with a matching transformer. (Remember the

diode resistance?) You could hear the signal with your ear close

to it, but this wasn't very useful. Now that I know about how much

signal I got in the headphones, I can try this at home with a

signal generator. Testing the loudspeaker project properly is one

for the next opportunity that I get for stringing up another long

wire, which will most likely be next Christmas when the site is

nice and quiet again.

Further Asides

The crystal earpieces tend not to fit

in your ear if you're a kid, can be quite uncomfortable and

instantly get covered in earwax regardless of the age of the user.

They're not very nice in this respect, especially if you plan to

share the earpiece and consequently any ear infections that you

might have.

If you're worrying about having the diode the wrong way round in

the circuit then don't. In a single diode crystal set you can have

it either way around and the listening result will be exactly the

same. You will just be using the opposite polarity half of the

radio waveform to produce the audio signal.

When visiting the Thamesmead estate in East London in the summer,

it occurred to me while supping an afternoon pint at the Lakeside

Bar (dead posh y'kno) that the three tower blocks on the opposite

side of the lake would make outrageously good anchor points for a

similar experiment, possibly even with two dipole arms meeting at

the block in the middle. One of which would go to the ground

connection on the set, and the other to the 'aerial'. But don't

try this at home, kids. Or at least make sure you're below

lightning conductor level.

I've completely neglected the reactive properties of the aerial

which could be tuned out, or perhaps more accurately stated tuned

in with more controls. But that would be frequency dependant and

we've already been down the two tuning controls route and decided

that's a bit of a fag. In practice, if you've hit a maximum on the

Mr. Slidey rod, this has already happened by interaction with the

main tuning capacitor.

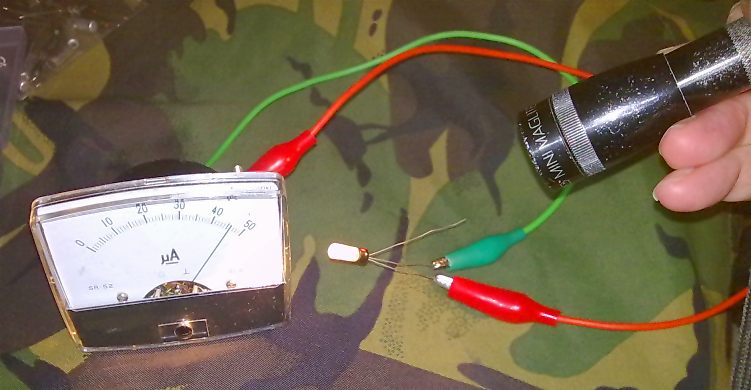

Some old germanium transistors have a transparent filling

underneath the black painted glass encapsulation. These will

actually generate 100uA of photocurrent when under a lamp or

certainly in sunlight. I once met a circuit in an old library book

from the 1960s which used just such an item in a Hartley

oscillator using a small audio output transformer. It would

oscillate audibly with no power applied into a crystal

earpiece when you shone a light onto it. I was impressed by this

piece of cleverness. So maybe you could even use an old OC45 as

the demodulating diode and get some gain out of such a crystal set

when there is light available. You could argue that this is

cheating by using an external power source, but if a candle or the

sun will work I think we're still qualifying. I've tried an

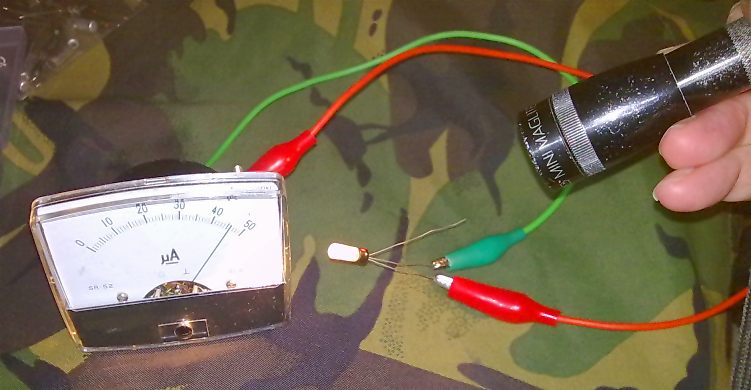

initial experiment as shown in the picture below where you can see

45uA coming out of just such a scraped-off OC45. The current is

measured between emitter and base and also occurs between base and

collector. The current is very dependant on finding the exact

sweet spot with the torch. It can go much higher than 50uA and I'm

sure in sunlight it would be higher still.

I tried using a transistor like this, with the base and collector

shorted, as a demodulator. The Vf was very low, about 200mV and

was louder than the best OA81 that I've found so far. It was

leakier in the reverse direction though. Shining a light onto it

made no magic difference, with strong or weak input signals, so

more fiddling with this is a project for the back burner. You can

get germanium junction diodes made in the Soviet Union back when.

They are good, too.

Glear Glass OC45 Germanium Transistor Generating Current In

Light

If anyone has tried and suffered "The Crappy" crystal radio set

design before, I hope this page offers some light. Those people in

the 1920s weren't so daft and they weren't necessarily straining

to listen to their crystal radio.

A 2026 Update Perspective

All those European LW stations have

gone. BBC Radio 4 on 198 kHz soldiers on. Algiers Chaine 3 from

North Africa is still there on 252 kHz radiating a spectacular 1.5

Megawatts from a full height quarter-wavelength mast at Tiapazia.

You can hear it on a proper LW radio in Southampton as a routine

daytime experience. It would be wonderful to see if that was

audible in the UK using this crystal radio set-up now that RTE

have vacated 252. It would also be wonderful to see what

you could hear at night. Virgin/Absolute radio on 1215

kHz etc. are long gone, dropping off-air under an Ofcom cloud when

their electricity bill got too expensive. BBC Five Live, Talk

Sport, BBC Wales, BBC Scotland, Caroline, Punjab, Lyca, and others

continue on AM MW in the UK.

There was an American mythbuster type programme on TV or Youtube

where they "busted the myth" (ooo, Hark, luvs!) that you could run

a 1.5V digital watch or calculator from a crystal set generating a

DC voltage. They weren't trying hard enough. You could easily do

it with this system, just by replacing the headphones with a 100nF

capacitor to smooth off the audio.

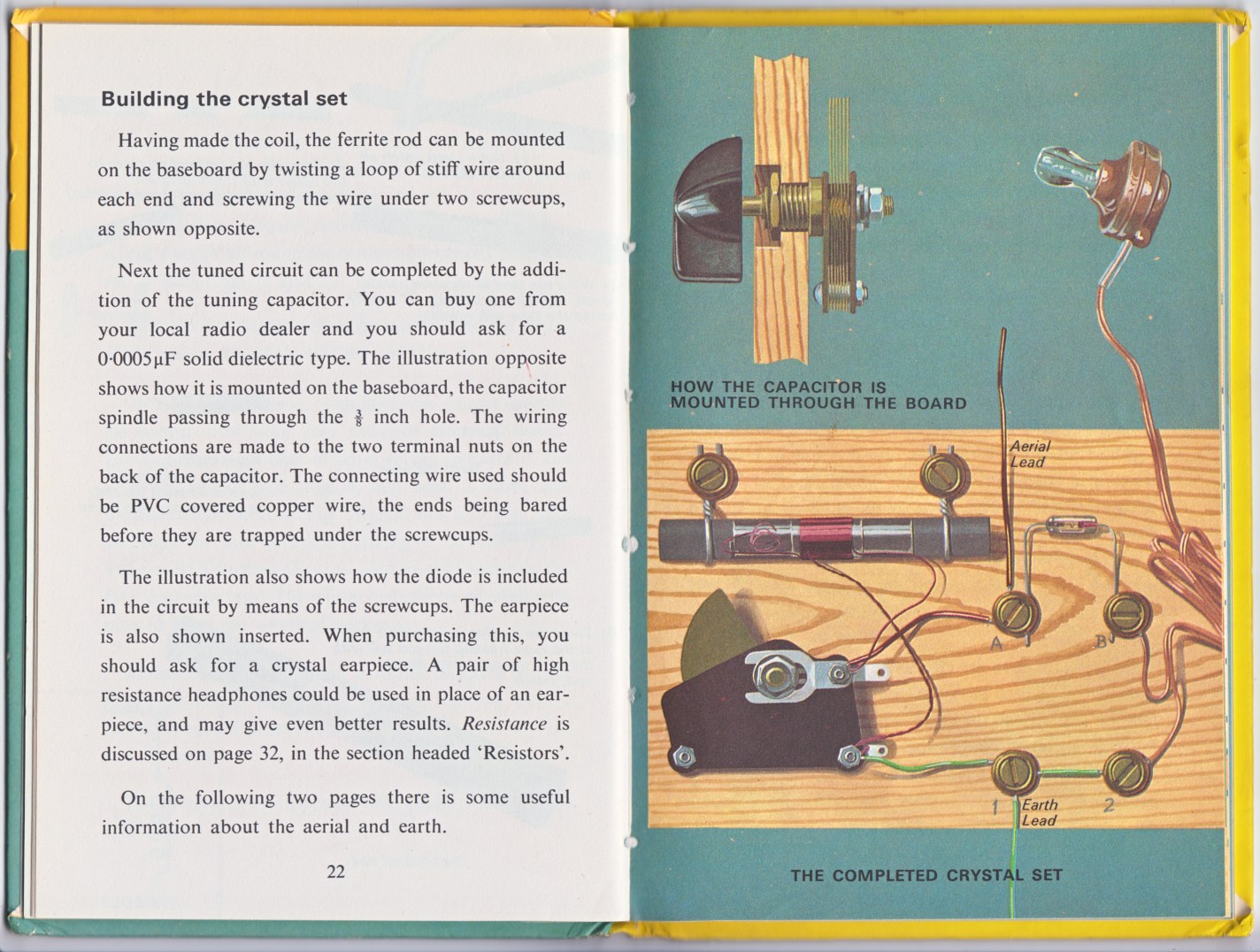

The Ladybird Not Very Good Crystal Set

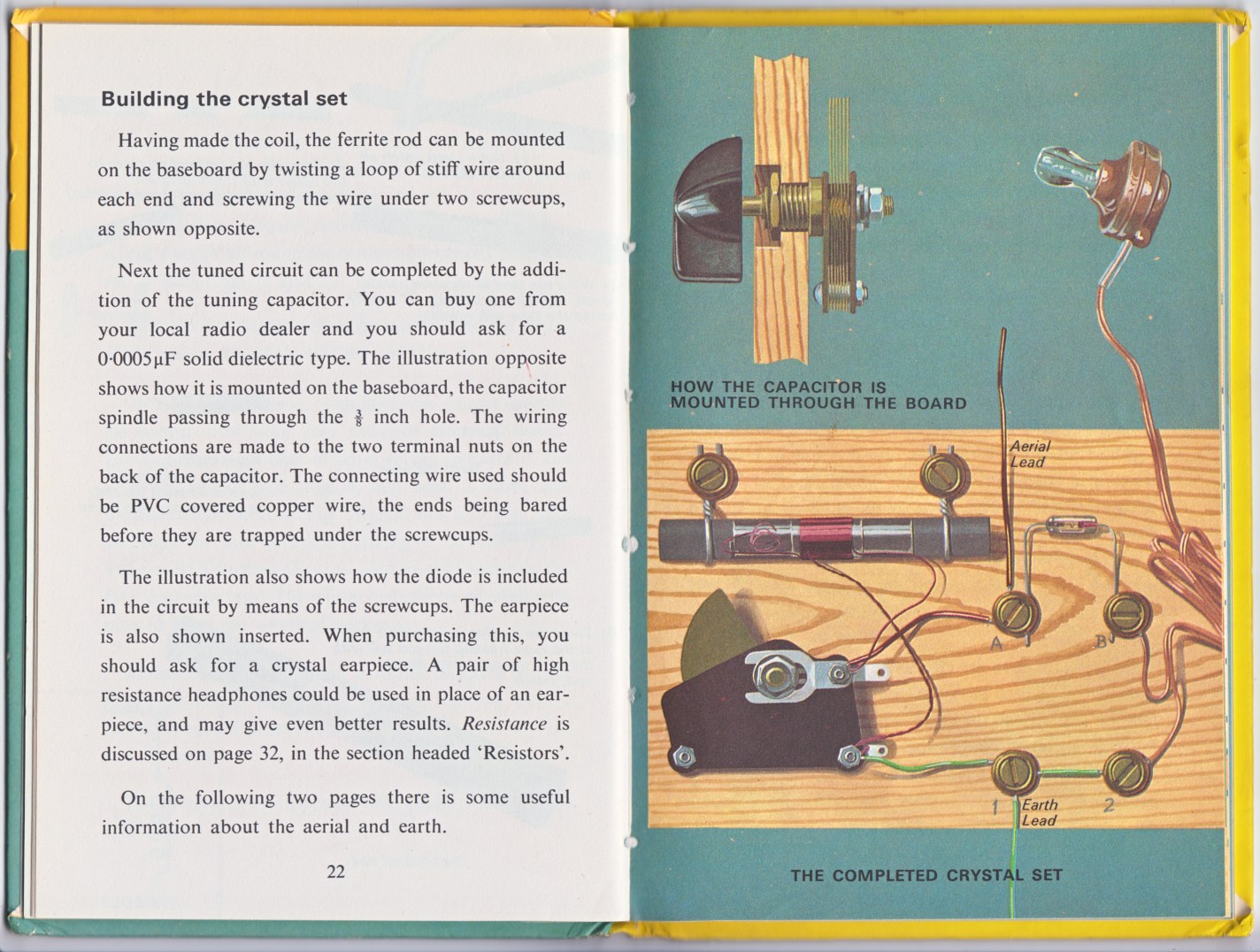

Here's the ladybird book not very good crystal set. I recently

noted that in this construction, apart from suffering from all the

problems mentioned above, the ferrite rod is secured to the

baseboard using two loops of conductive wire. That's two shorted

turns around the rod killing your signal and ruining the

selectivity. Arrrrrgh! Infuriating. Use PVC insulation or anything

non-conductive. I used some PVC terry clips.

To quote page 22, "A pair of high resistance headphones could be

used in place of an earpiece, and may give even better results."

Could. Could? May? Have you actually even bothered

to try it? No. Infuriating:)

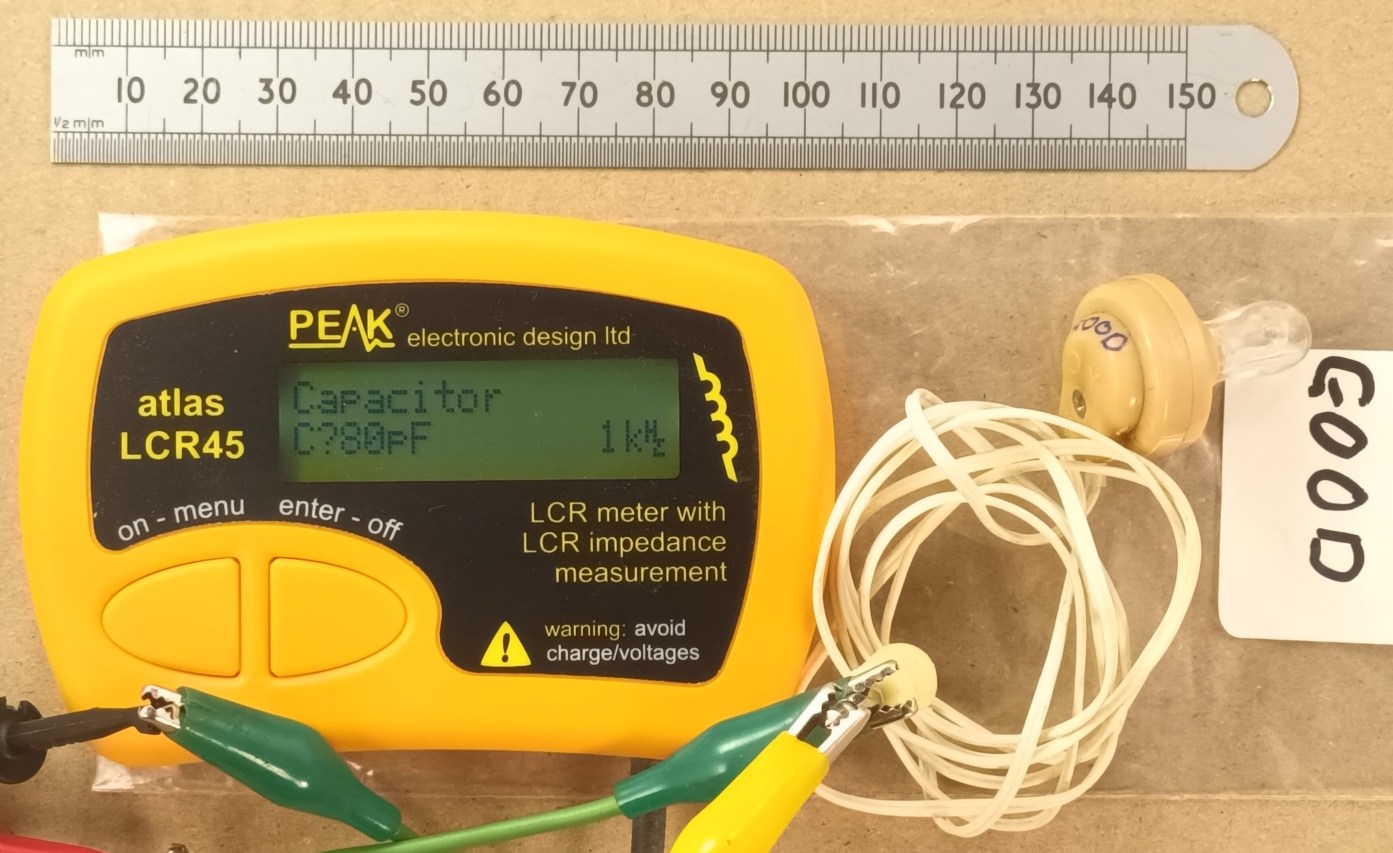

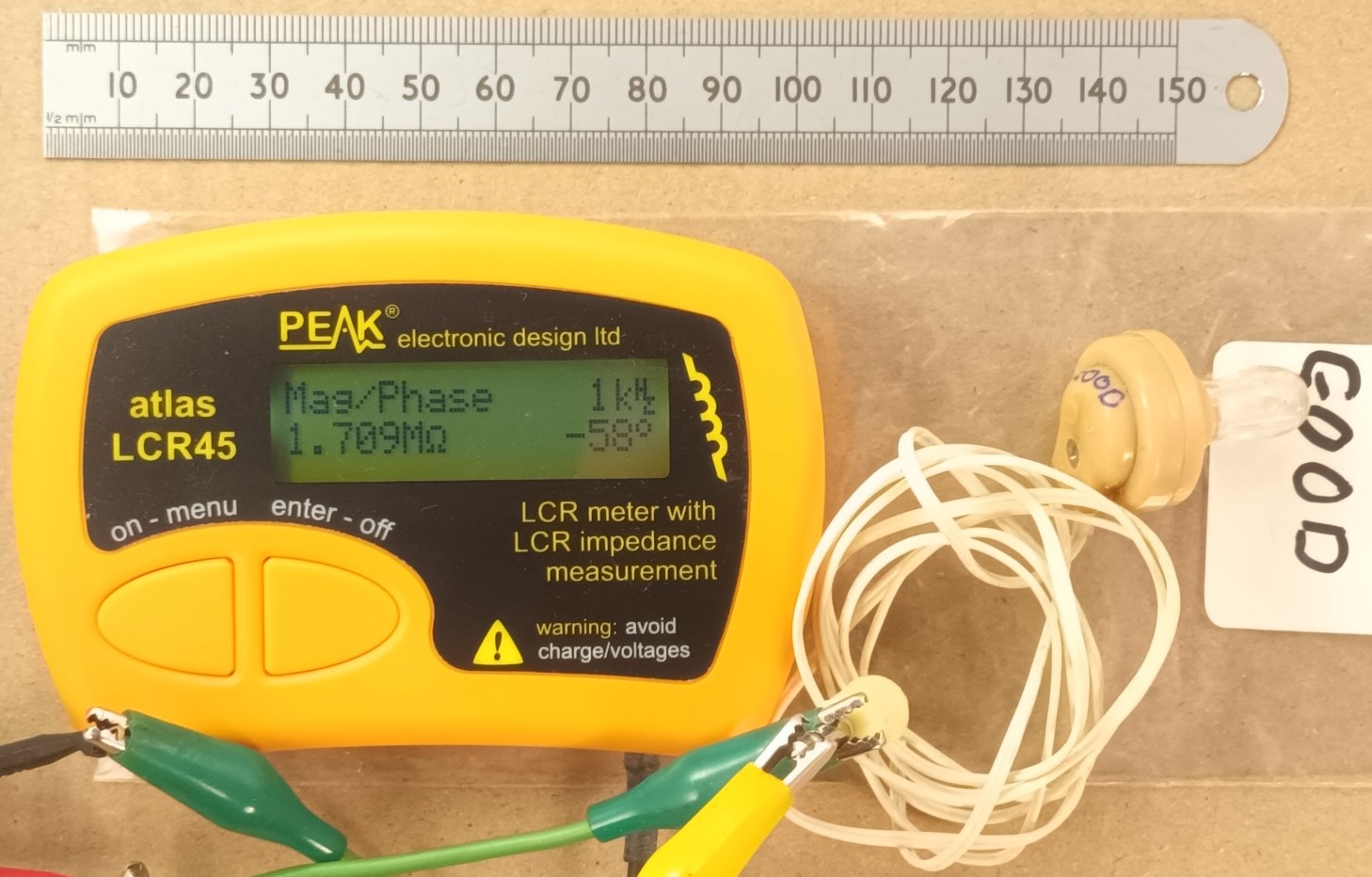

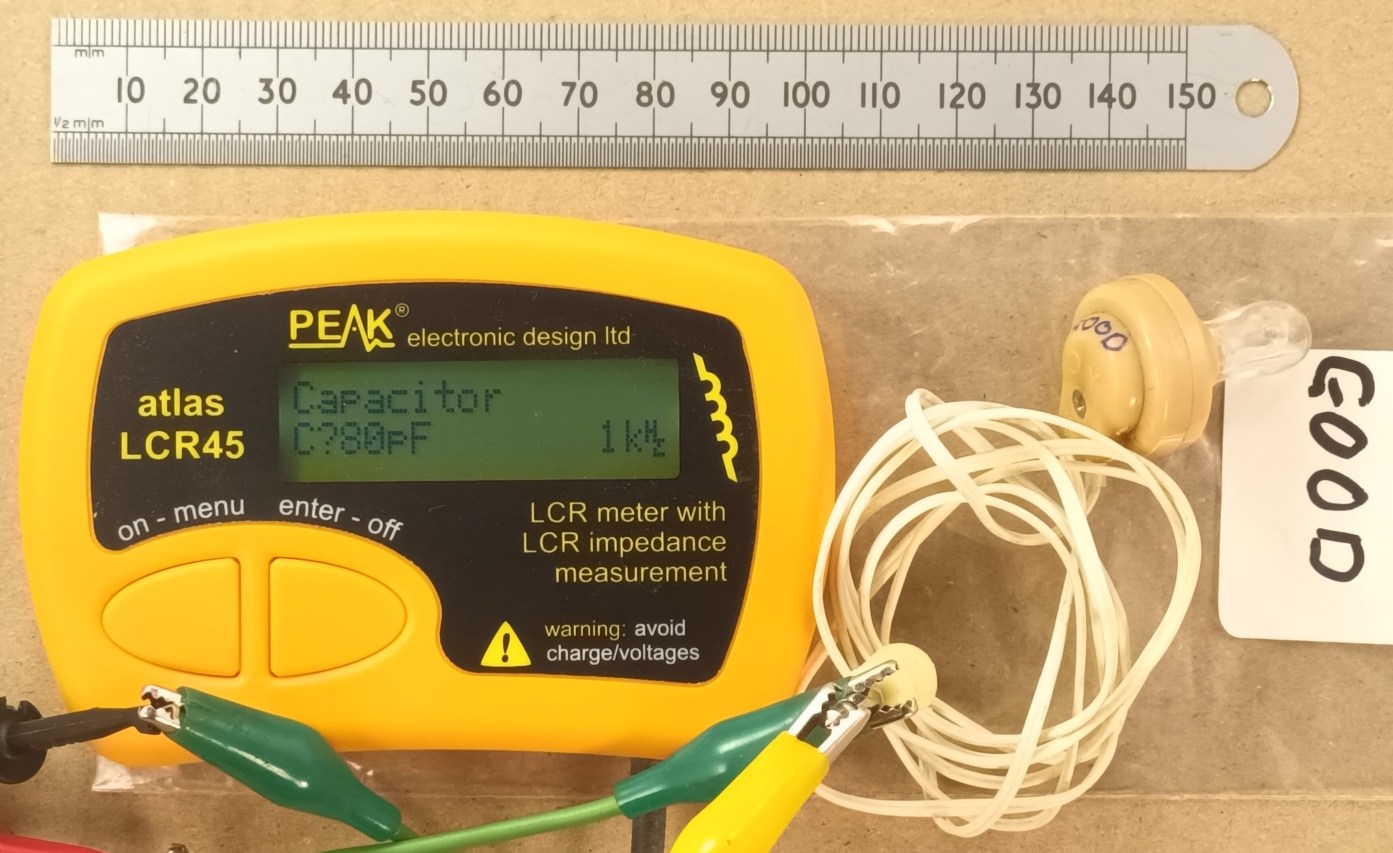

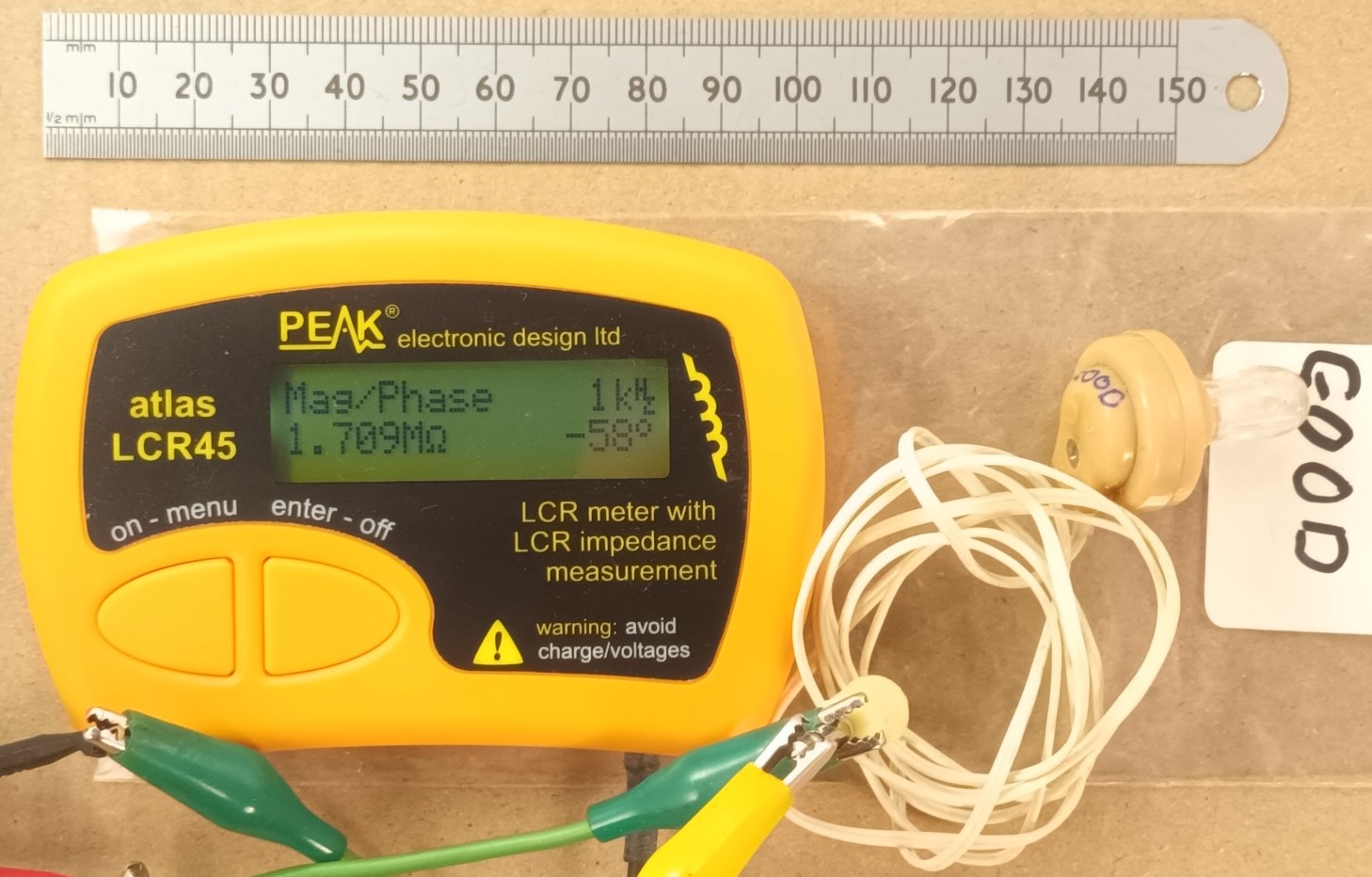

Older Crystal Earpieces

I've recently found a few of the older type crystal earpieces at a

radio rally. They are highly variable and have probably aged

badly. I've been informed that the Rochelle salt crystal used in

them is hygroscopic. The crystal absorbs water over time and tends

to turn into dust, so watch out if you're offered a bag of

hundreds of them. A few good ones measure about 80pF, 60M

resistive, and have similar if not better sensitivity than the

modern ceramic element ones. You can hear a decent level of mains

hum just by grounding the plug sleeve and putting your finger on

the tip. You can see the test results below, though it's a pretty

low capacitance for a precise measurement.

Old Proper Piezo Crystal Eapiece Capacitance Test At 1kHz

Old Proper Piezo Crystal Earpiece Mag Phase Reading At 1kHz

Henry's general email address:

Navigate

Up

Recent

Edit History

01-FEB-2010: page created

21-JAN-2025: bit of an update

28-JAN-2026: major update, html incantations, direct refs,

bigger pictures